This interview was conducted in Ramallah, Palestine on 16 June 2015 following the local and international release of Amer Shomali’s film, The Wanted 18, which opens in US theaters on 19 June 2015.

Isis Nusair (IN): Where did the idea of the film come from?

Amer Shomali (AS): I grew up in the Yarmouk [Refugee] Camp in Syria. During the first intifada (in 1987), my parents would tell me stories about Palestine. As a kid, they could not tell me all that was happening. I remember one story about an uncle who was arrested by the Israeli authorities after he was hiding in a palm tree! These stories about Palestine and the nature of the people stayed with me. I was obsessed at the time with superheroes and comic books like Asterix and Tintin. I understood Palestine through these books; it was an illogical and imaginary place for me.

When we returned [to Palestine] after the Oslo Accords in 1997, there was disappointment and shock. Palestine was not what I imagined. Then I met someone from Beit Sahour who told me, “everything you imagined about the first intifada was real but you came at the wrong time.” The Wanted 18 is a film that transports the audience back into that period, where they can relive those experiences. I found out that even the people of Beit Sahour themselves had the desire to live through that period. They opened their houses to the crew and provided us with archival material of pictures and home movies. They helped in all the details of making the film. They would advise on which of their children should play their roles, how they should dress, and how to represent the first intifada.

IN: The film comes across as a theatrical performance enacted by the people of Beit Sahour.

AS: I wanted to recreate the intifada in a theatrical way and see how the different generations would interact with each other. People were so engaged with the film and every house became like a studio. They would invite us over, and prepare a cup of tea before we started shooting. The people of Beit Sahour claimed the film and its discourse. It took five years to complete the research for the film. We used to share the stories with the people and they would become part of the process of documenting the history. The town became like one big operation room.

At the last day of shooting we were supposed to film a demonstration. We needed fifty people. Early that morning, I appeared at the local radio station and requested an intifada song. I asked people on the air to come dressed in dark clothes for the scene. Two hundred people showed up and many of them became like assistant directors giving us advice on how things needed to be. This gave them ownership over the narrative of the film.

IN: What about the ending of the film?

AS: I left the ending of the film open, where one of the cows is ready to return at any time if we are willing to go into the desert and look for her. It is the same desert the youth of the first intifada used to escape and hide from the Israeli soldiers and later from the Oslo process, and where Jesus sought refuge.

IN: There is a thin line between fiction and documentary in the film.

AS: We do not have an archive of the first intifada. We have an archive filmed by foreign crews. The dominant image of the first intifada was of Israeli soldiers breaking the hands of Palestinians and of Palestinian children throwing stones at Israeli soldiers. There were no images, for example, of Palestinians milking cows. The civil disobedience was an attempt to separate from the Israeli occupation, and the animation in the film is an attempt to create an alternative archive. The film tells the story from the memory and point of view of the cows. It is easy at times for the “West” to identify with the cows more than with Palestinians. The film is a story of how the cows lived under the Israeli occupation.

.jpg)

IN: What about gender relations in the film?

AS: Anton’s mom, her sister and Siham are very powerful characters in the film. People used to tell us their stories and cry. Even men cried except for Anton’s mom. It is as if the tears had dried in her eyes. As we were preparing for the film and consulting people, women had a different point of view to share. They were the ones who told us, for example, about the cow that was crying as she gave birth. The way Siham told the story opens new venues for empathy. Women during the first intifada were taking leading roles and were at the frontlines of demonstrations against the (Israeli) occupation.

IN: Why is it important for you to express that longing for the first intifada?

AS: I feel selfish for being able to create that period and be in touch with my childhood memories and history. The film is not regressive and does not idealize the past. It is an attempt to understand the past in order to be able to move forward. People at the time wanted a third option; an alternative. The two extreme options that were available were either to emigrate or explode. I do not want to be part of the occupation machinery and the solutions imposed on us. That is where the longing for the past comes from.

IN: How does your film connect to the current Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement?

AS: I studied at Birzeit University and in Canada and Britain. I designed some posters for the initial boycott movement (available at www.amershomali.info). Today the movement is stronger conceptually. During the first intifada, they wanted to create alternatives and that is where the idea for civil disobedience came from. Currently, there is no clear Palestinian national and local project, yet internationally, and with the help of the BDS movement, there is more awareness. People have a role to play and it is great to see them play that role. The boycott is not only about Israel but about fair trade and creating different alternatives and standards of living. We are part of this process.

IN: How was the experience of co-directing the film with the Canadian Paul Cowan?

AS: Paul and I are different in age and in our sense of humor and this became an added value to the film in terms of having a solid structure and narrative. I wanted it to be a comedy and a fantasy-like movie. We reached a common place where the context of the film became clear to the audience and where Westerners could understand it without it becoming too boring for Palestinians. There is a thin line between comedy and fantasy. One of the scenes in the film is similar to The Godfather, and in another [Yasser] Arafat resembles [Theodore] Herzl as he dreams of the future state. It is interesting to see in each screening what people find funny and what shakes them to the core.

I publish comic strips in al-Safir and al-Akhbar newspapers. I use comedy as a way to reach people. Those who are unable to make fun of their wounds are unable to heal them. I wanted to convey our issues in an honest way. I am looking for empathy and not sympathy, and for the audience to put themselves in the position of the cows and understand why they think the way they do. The film is not educational, it is supposed to be fictional and entertaining. The characters collapse after twelve minutes as in Hollywood action films. The cows are like a Trojan Horse. You start to love them and then you feel stuck as you might start loving the Palestinians as well! Historically, we were represented in Hollywood films in a very negative way. I am hijacking the same Hollywood structure and visuals to tell a story that is opposite to what is usually told.

IN: You were denied permit recently by the Israeli authorities to get to the American Consulate in Jerusalem to obtain a visa for the screening of the film at the Human Rights Watch Film Festival in New York.

AS: More than fifty percent of the requests to enter Jerusalem are denied on the basis of security. I could leave the country through Amman but I am denied access to Jerusalem that is only several kilometers away. This is about collective punishment and not security threats. Even the cows in the film are a security threat!

IN: How was the film received?

AS: The film was screened at the Toronto Film Festival last September and since then it had participated in film festivals in Abu Dhabi, Carthage, Lyon, and Addis Ababa among others. The response has been amazing. Half of the audience for the film is usually Jewish. One woman told me recently, “I am Jewish and I am glad I saw the film. I never saw this side of Palestinians and of Israel.” I wonder what kind of propaganda films she has been seeing where the educated Palestinian who is dressed nicely and wants to improve his situation does not exist, and where there is no mention of Israel chasing cows (as a security threat)!

IN: How did you get access to interview the military governor and his deputy?

AS: It was important for me to interview the Israeli military governor of Beit Sahour during the first Intifada. We were denied access to the Israeli military archives and to how they used to confiscate people’s furniture. In the end, we were able to reach the military governor and his deputy and asked them several questions about the first intifada including some about the cows!

Film Trailer

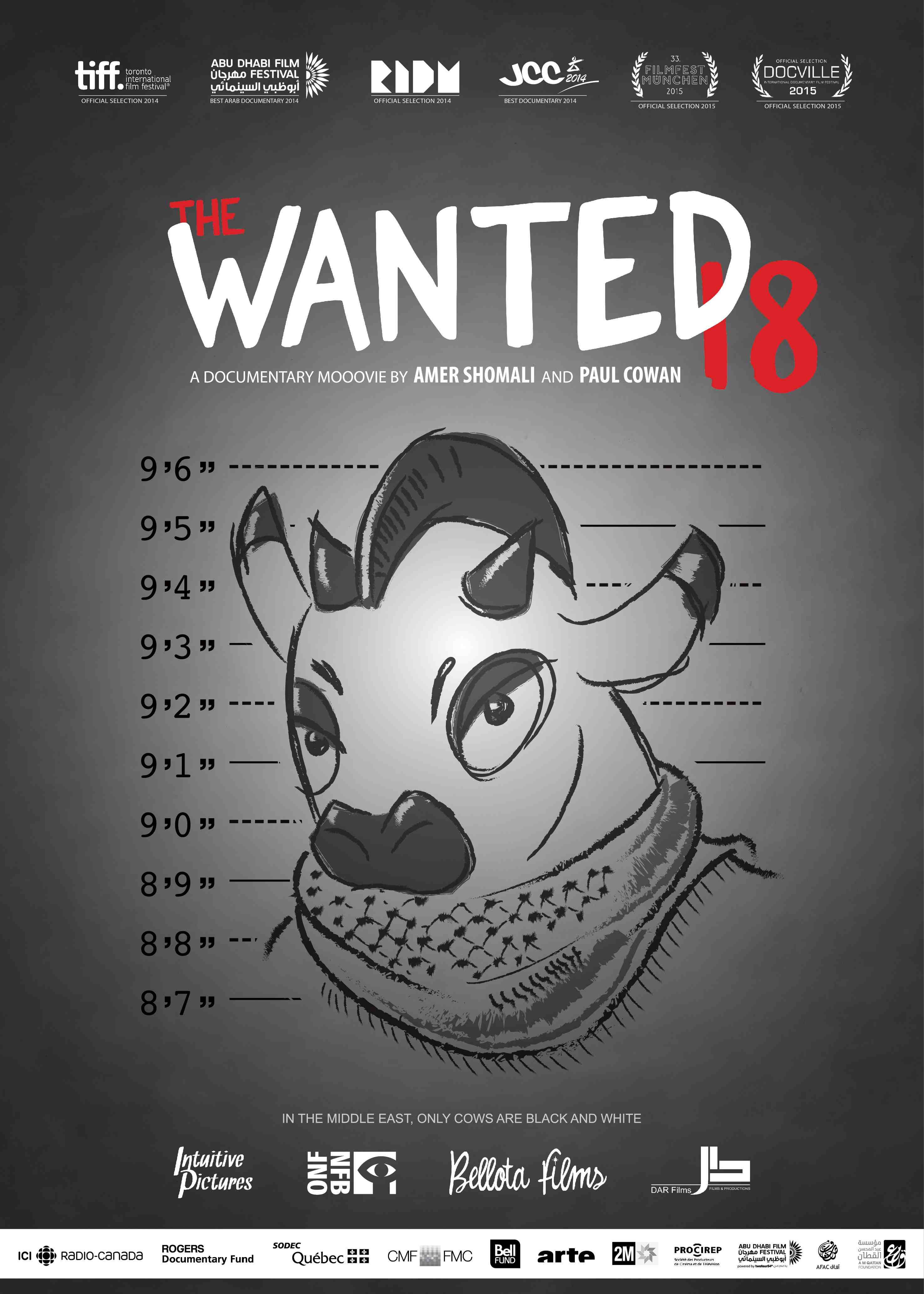

Film Poster